July 10th, 2014

Game Changer Blog: If U.S. College Tennis Were An Ice Cream Flavor? Rocky Road?

Americans are using college tennis as a pro springboard — but can it last in the ever-changing pro and college landscape?

U.S. colleges and universities are once again the training grounds for the professional tennis ranks. But what’s changed to make school cool again for aspiring pros, after an era where playing NCAA tennis was looked down upon?

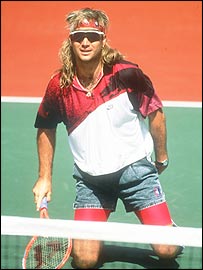

The mid-’80s saw young pros like Andre Agassi making jumps straight to the pros — while making aforethought impossible fashion combinations such as jean shorts and pink bicycling pants

Beginning around the mid-1980s, college tennis was starting to be seen as a last resort for kids who couldn’t make it on tour, and likely never would due to the distractions of college, and what was then seen as a lower level of competition.

Today, due to a number of factors, college tennis is once again seen as an incubator for some of the top pro prospects, especially those late to mature physically (or mentally). In fact two of the current Top 3 U.S. players, as of the July 7 ATP Rankings, at one point played college tennis.

But what changed?

AGASSI AND PALS CHANGE THE PRO LANDSCAPE

Prior to the 1980s, since the Open Era of pro tennis began in 1968, almost every U.S. male player went the NCAA route before taking to the pro tour. The “Bollettieri Generation” changed all that.

Bollettieri Academy products Andre Agassi, Jim Courier, David Wheaton and others, along with non-Nick products Pete Sampras and Michael Chang, launched straight from the junior ranks to the pros in the late 1980s and early ‘90s. Outspoken coaches such as Bollettieri, Robert Lansdorp and a few select others had tapped into the fountain of youth.

Girls mature faster than boys, and young phenoms such as Chris Evert and Jennifer Capriati cracking the Top 10 as teens were the norm. But teenage boys — who could now compete with men? Tennis had been turned on its head, and college was now seen as at worst a failure, and at best a stopover with little chance of making it out.

But that would also change.

Bigger-hitting racquet and string technology were starting to favor older players. Young players with still-maturing bodies were having a tougher time, and the average age of tour players was rising.

TECHNOLOGY (NOT YOUR iPHONE) FAVORS THE OLDSTERS

In the 2000s technology was beginning to radically change tennis. “Super” racquets and even super strings made strong players even stronger, making it harder for young players to keep up.

Today top players like Serena Williams, Li Na, Tommy Haas and David Ferrer are still accumulating titles well into their 30s. “Compared to 20 years ago, I think guys can hit the ball bigger now,” American Sam Querrey said last year.

“A man can just overpower and blow away an 18-year-old boy…[Back then] you couldn’t hit the ball through players as much, so it allowed some of the younger players to feel their way into the game.” Andy Roddick was an anomaly, a player with a ready-made huge serve and forehand who ushered in the era of the “super racquet” with the Babolat he had played with as a junior, before the ball-crushing Babolat conquered the U.S. market.

When Roddick hit Pete Sampras in the chest with the “serve heard ‘round the world,” it was the sign of a new generation – but not one that could reach the impossible heights of the former.

Roddick, Mardy Fish and Robby Ginepri followed the Bollettieri Generation right from the juniors to the pros, and coaches thought it would be more of the same – more world No. 1s like Sampras, Agassi and Courier — but that “rush them to the head of the class” philosophy had already begun to change.

PAT MAC SEES THE SHIFT

A few years ago, soon after coming on board with the USTA as general manager of professional development, Patrick McEnroe, who helped Stanford to two NCAA team titles before turning pro, admitted the USTA erred in their professional development strategy.

“We in the USTA maybe made a little mistake in pushing some of our junior prospects to go straight to the pros in the past,” said McEnroe, who wholeheartedly endorses college for the majority of junior players. “I think we lost a group who, if they had gone to college and had a chance to mature in every category, would still have had a chance to be a high-level professional.”

Isner, the current top American, has become the poster child for college tennis development after spending four years at the University of Georgia.

“You see guys coming into their own at [age] 25, 26,” Isner said. “Wasn’t like that 10, 15, 20 years ago. College was perfect for me, and seems like it’s working for a lot of other players as well.”

College tennis is working for Americans again – but a question asked 20 years ago that is an even bigger controversy today — can U.S. players even make the team?

U.S. NOW THE MINORITY AT TOP LEVELS OF U.S. COLLEGE TENNIS

In addition to technology changing the pro tour and driving more kids toward college, NCAA tennis has also changed – for better or worse.

The uninhibited influx of international students into U.S. college tennis over the years has consistently upped the talent ante, and pressure, for college coaches. To compete, many teams now boast line-ups of all-international starters. And with the NCAA’s difficulties in tracking obscure tournament or pro league results, a number of international players get away with playing pro-level tennis before deciding that accepting a four-year U.S. college scholarship is an easier way to continue to play and train.

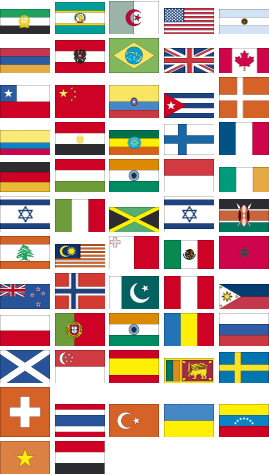

The NCAA has refused to put a cap on the number of international players allowed on a team. At the Division I level, more than half of the starters on men’s and women’s teams are international players. The result is that the current U.S. college tennis landscape resembles a United Nations of players, and the talent level has grown to resemble the lower levels of the pro tour.

Proponents of the shift point to the “rising tide” philosophy – that the rising tide lifts all boats, that U.S. college players are forced to get better, to keep up, to improve. Ironically it’s the U.S. college system that is now developing the stars of tomorrow for many other countries. In the second round at Wimbledon this year were No. 20 seed Kevin Anderson (University of Illinois) of South Africa, recent Ohio State graduate Blaz Rola of Slovenia, and Germans Benjamin Becker (Baylor) and Tim Puetz (Auburn).

And it is unlikely to stop.

“The junior colleges have adopted a two-foreign-player-per-team rule and it has been quite successful,” says four-time college coach of the year Chuck Kriese, an advocate of limiting international players on college teams. But the NCAA is a whole other governing body, and has shown no interest in limiting international players, still bruising from a long-ago but well-publicized former incident.

An attempt by the NCAA in the 1970s to limit the number of international students in track was labeled discrimination, and the NCAA is seen as unwilling to again enter into that arena.

TOP JUNIORS GET AN EARLY LOOK AT COLLEGE

But the USTA and Patrick McEnroe have taken advantage of the current competitive college climate to not only attempt to develop potential future U.S. stars, but to give U.S. juniors a preview of college tennis.

USTA/ITA (Intercollegiate Tennis Association) Campus Showdowns on college campuses across the country invite everyone from juniors to college players to adults to compete against each other in one-day formats.

The ITA Summer Circuit has events throughout the U.S. where juniors, college players and others can compete in regional events during the summer school break, wrapping up with the ITA/USTA Summer National Collegiate Championships. The top U.S. juniors also annually compete in special invitational USTA events against college teams, and the top U.S. college players compete on the USTA Collegiate Team, traveling together to USTA Pro Circuit events and taking advantage of elite training and coaching opportunities before heading back to school in the fall.

TODAY’S COLLEGE EXPERIENCE

Florida’s Alexa Guarachi, who played for the University of Alabama, said college tennis was a surprise in regard to the opportunities it offered.

“I would tell a junior girl facing this decision that going to college doesn’t mean you won’t go pro,” Guarachi told the Tennis Recruiting Network. “I faced the same decision, and I almost felt like I failed in a sense — that college was such a step down. But it truly wasn’t. Going to college was one of the best decisions of my life. Some people don’t have the money or opportunities to have their own athletic trainers, coaches, and fitness coaches at their disposal. At any college, you will have all those opportunities — as well as teammates that can push you every day to help you improve. Also the quality of competition you face in college is so high.”

Outside of exceptional physical talents such as Andy Roddick or Sam Querrey who can make a quick leap from the juniors to the pros, Isner agrees college is the right path.

“We’re seeing it now, and I think we’ll still see is quite a bit in the future,” Isner said about current pros with collegiate experience. “I think especially for American players coming up, I think college is a good choice. Maybe [at] the very minimum for one or two years.”

When the USTA Orlando “Home of American Tennis” is completed in late 2016, it will further bring together entities that were once seen as separate – professional development of top juniors, college players and existing pros, all under the same roof taking advantage of the top coaches, training, and technology at the most advanced facility in the U.S.

Until the next 16-year-olds punch through straight to the pro ranks with the next line of bazooka racquets, it looks like school is cool again.

What do you think about the current U.S. college climate, the world catching up to the U.S. over the past 20 years (and the changing face of pro tennis), and professional development of junior players moving forward? Share your opinions or ideas in the comment section below.